Inspired by last week’s post on the use of granite (and what is called “granite” but not really granite) in countertops, we are going to focus this week’s post on another rock that you may have heard of in the commercial sector: slate (and rocks pretending to be slate).

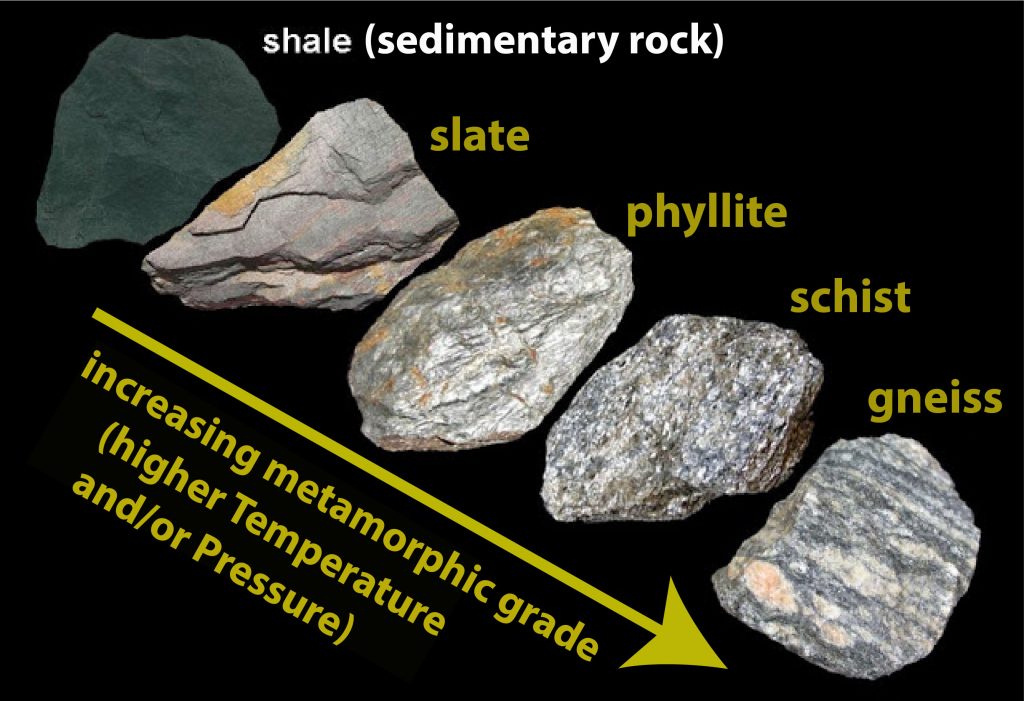

You are likely most familiar with slate through a number of different products: slate chalkboards, slate roofing tiles, or slate paving stones1. Slate is most commonly formed when a fine-grained sedimentary rock like shale undergoes physical and chemical changes due to increases in temperature and pressure. So what kind of rock is slate? Loyal readers of Backyard Geology should be jumping out of their seats right now with the answer: slates are metamorphic rocks! (Nice one, loyal readers!) We’ve talked about metamorphic rocks a few times now, focusing in on some minerals that are formed during metamorphism (featuring Jess’ favorite mineral: garnet) and some crazy structures that can result from the stretching of rock layers during metamorphism (boudins!).

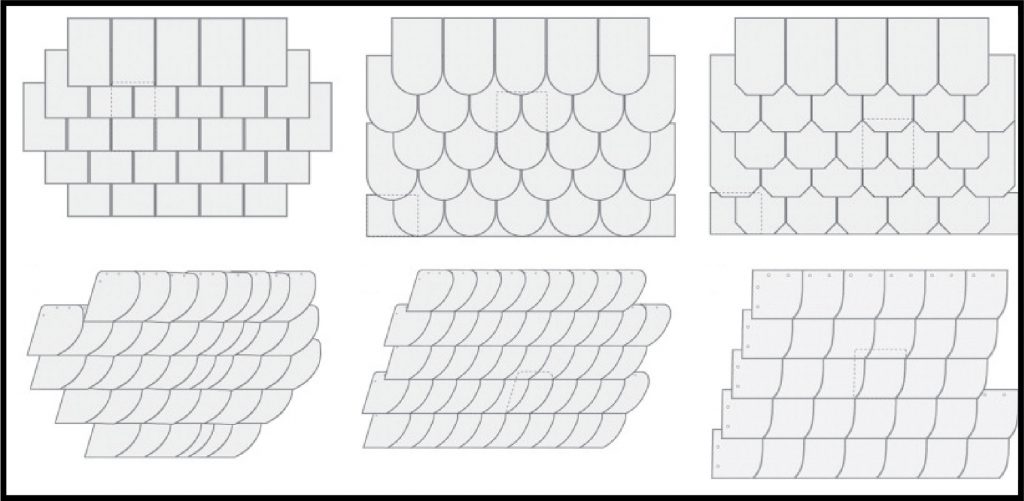

Take a moment and picture a slate chalkboard or the tiles making up a slate roof. How would you describe them? Probably one of the first things that you think of is: a thin, hard sheet of rock. In fact, that is the main feature that the commercial industry uses to describe the rock that is mined for slate building materials. For example, roofing slate is defined as rock that can be easily split into thin tiles1. But, just like our igneous friend, granite, and its use in countertops, “slate” is often a catchall industry term for many different types of rocks from a geologist’s perspective.

Let’s focus in on what could give a rock like slate the ability to be broken into these thin sheets. One of the major mineral groups making up slate are the micas (these include minerals you may have heard of like muscovite, biotite, and/or chlorite). Micas are often shiny because they are minerals that break into sheets, resulting in big reflective surfaces. When you see a really shiny, beautiful rock it likely has mica in it. So, slate contains minerals that like to break into sheets. But remember…slate is also a metamorphic rock! When rocks are squeezed under higher temperatures and pressures, this causes the minerals in the rock to align and form a special layering (or fabric) called foliation. In the case of slate, this foliation results in the thin sheets that make slate a perfect material for tile!

A geologist’s version of slate vs. “roofing slate”

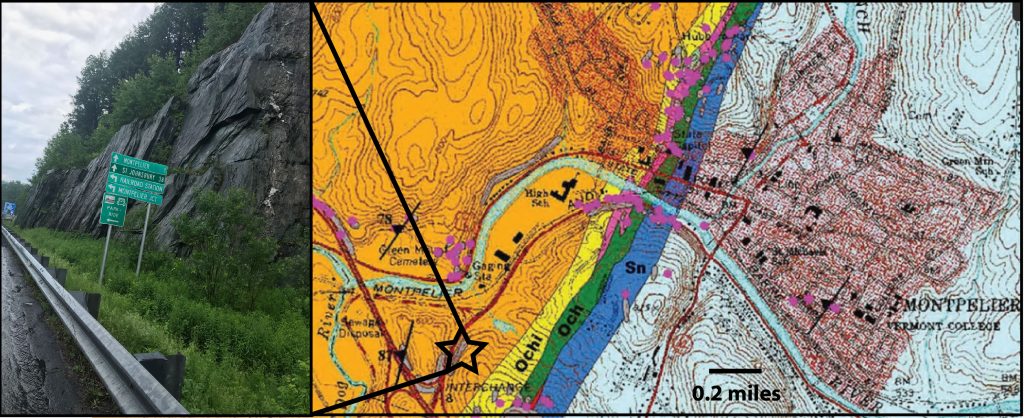

This weekend, I traveled to Vermont for my brother’s wedding (congrats, Daniel and Ally!). If you ever drive through Vermont, you will notice that the edge of the highway is lined with rock outcrops. Vermont is like New York (and many other Northeastern states) in that it is absolutely covered with metamorphic rocks. Up by Montpelier, Vermont (which I was told this weekend is the smallest state capital in the country), you will notice rocks along the edge of the highway that have a very slate-like appearance: hello, sheety layers aka foliation! The Montpelier area has been home to numerous slate quarries in the past, including the Sabin Slate Quarry. The Sabin Slate Quarry ran from around 1870 – 1887, becoming increasingly profitable after the Montpelier “Great Fire” in 1875 when non-flammable building materials like slate roofing tiles were highly sought after2. The rocks used to produce this roofing slate were durable and easily broken into thin sheets: perfect slate! There’s just one little problem. From a geologist’s point of view, this rock isn’t really “slate” but “phyllite”.

Phyllite is a pretty close relative of slate. Phyllite is made from a sedimentary rock that has been metamorphosed under higher temperatures and pressures than slate (we say that it has a higher metamorphic “grade”). This brings us to our deep-dive into what geologists call slate and “roofing slate”. Technically, “roofing slate” can be what we in the geology world call actual slate, phyllite, or schists (another type of metamorphic rock). “Roofing slate” can even be a sedimentary rock like shale1! As long as the rock is durable and breaks into tiles, it will serve the purpose of the roofing slate industry.

Think back to the first picture we showed you of a rock outcrop along I-89 just south of Montpelier, Vermont. This rock is actually phyllite and is part of the Waits River Formation, which formed during the Silurian to Devonian Periods5. See the video of what this rock looks like as you zoom by it on the highway below!

Video by: Kristen Rahilly, Driving by: Dan Rahilly

References:

1Cárdenes, Victor, et al. “Petrography of roofing slates.” Earth-Science Reviews 138 (2014): 435-453.

2Heller, Paul. “Sabin’s Slate Co. was big business.” The Times Argus, 04 January, 2016. Accessed 30 June, 2021.

3Kim, J., et al. “Bedrock Geology of the Montpelier quadrangle.” Vermont Geological Survey Open File Map VG03-1 (2003).

4Geology In. Regional Metamorphism: The Formation of Foliated Metamorphic Rocks. http://www.geologyin.com/2014/05/the-formation-of-foliated-metamorphic.html, accessed 30 June, 2021.

5Walsh, Gregory J., et al. Bedrock geologic map of the Montpelier and Barre West quadrangles, Washington and Orange counties, Vermont. No. 3111. US Geological Survey, 2010.