Would you like to impress your friends with a really cool sounding geological term? While we here at Backyard Geology make it our mission to convince you that everything about geology is cool and impressive, there really is something special (and just a little random) about a term that translates to “sausage” in French1. That’s right, Francophiles! This week, we are covering boudins and the feature known as boudinage.

Just in case your French is a bit rusty (or non-existent like my own), “boudin” roughly translates to sausage. In geology, boudins or boudinage is a feature mostly found in metamorphic rocks. We first mentioned metamorphic rocks in our post about the wonders of garnet, a mineral often found in rocks that have undergone both physical and chemical changes due to high temperatures and pressures associated with metamorphism. If you find boudins in a rock, it’s a good sign that the rock has been deformed through metamorphism. But how exactly do boudins form?

What taffy teaches us about brittle-ductile deformation

Boudins (or the overall feature boudinage) are a testament to the power of brittle vs. ductile deformation. One of the best ways to understand the difference between these two things is to picture a piece of laffy taffy….you know, one of those brightly colored taffy candies in the little individual wrappers. You have one of these candies in your pocket on a warm summer day (easy to imagine nowadays here in the Northeastern United States). When you finally get around to eating the taffy, you try to break a smaller piece off but the candy just stretches thinner and thinner without breaking. The taffy is undergoing ductile deformation! Now, how would you make the taffy break rather than stretch into a thinner piece? If you pop that taffy into the freezer, after some time the taffy will deform in a brittle fashion. If you were to hit the taffy with a hammer (for some reason), the taffy will fracture in a brittle manner like glass.

How do boudins form in rocks?

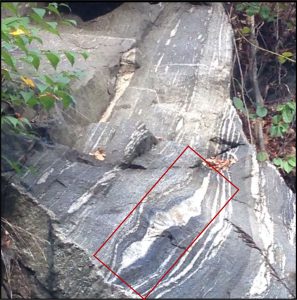

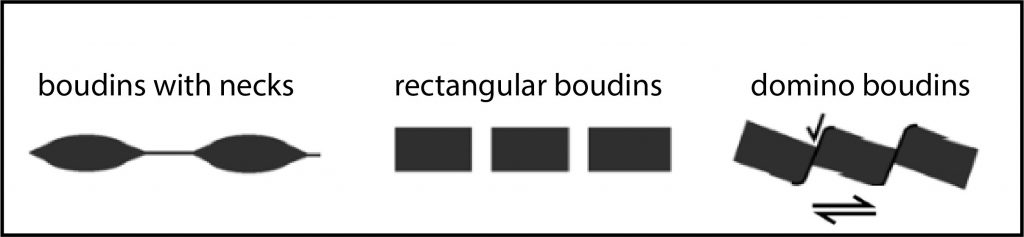

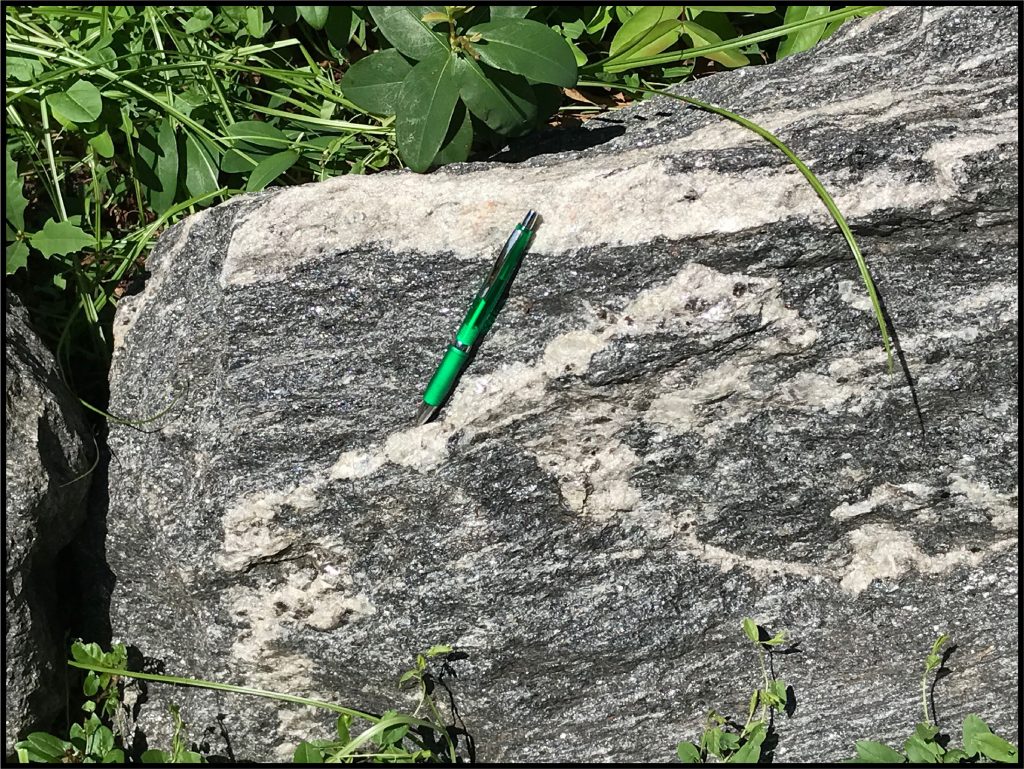

Boudins result when a layer, mineral vein, or some other planar feature within a rock is stronger than the other parts of the rock surrounding it1. This stronger layer is called the “competent” layer2,3. Boudinage occurs when rocks undergo extension, or stretching. As the rock is stretched, the competent layer will deform in a more brittle fashion whereas the surrounding rock will undergo more ductile deformation. After all this extension and stretching, the overall shape of the competent layer will depend on just how brittle it deforms. A layer with completely brittle deformation will form rectangular, separated boudins. A competent layer that undergoes both brittle and ductile deformation will form boudins that have little necks between them4. Sometimes things will get really crazy. If there are other forces pushing or pulling on the rock, boudins might be tilted, forming “domino” boudins3.

So boudins represent a complicated mix of both external and internal forces on a rock. They give geologists a clue as to what type of deformation the rock has undergone and the ancient forces that have played a part in that deformation. If you are ever in an area rich with metamorphic rocks, see if you can spot the boudins. Now you will be able to very confidently say that you know how the sausage (or “boudin”) was made.

References:

1Voight, B. 1987. “Boudinage”. In The Encyclopedia of Structural Geology and Plate Tectonics, Edited by: Seyfert, C. K. 33–41. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

2Strekeisen, Alex. “Boudinage” http://www.alexstrekeisen.it/english/meta/boudinage.php, accessed 15 June, 2021

3Goscombe, B.D., Passchier, C.W. and Hand, M., 2004. Boudinage classification: end-member boudin types and modified boudin structures. Journal of structural Geology, 26(4), pp.739-763.

4Fossen, H., 2010. Structural geology. Cambridge University Press.